From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Illustration of Hypersonic Test Vehicle (HTV) 2 reentry phase

The DARPA Falcon Project (Force Application and Launch from CONtinental United States) is a two-part joint project between the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the United States Air Force (USAF) and is part of Prompt Global Strike.[1] One part of the program aims to develop a reusable, rapid-strike Hypersonic Weapon System (HWS), now retitled the Hypersonic Cruise Vehicle

(HCV), and the other is for the development of a launch system capable

of accelerating an HCV to cruise speeds, as well as launching small

satellites into earth orbit. This two-part program was announced in 2003

and continued into 2006.[2]

Blackswift was a project announced under the Falcon banner

using a fighter-sized unmanned aircraft which would take off from a

runway and accelerate to Mach 6 before completing its mission and landing again. The memo of understanding

between DARPA and the USAF on Blackswift—also known as the HTV-3X—was

signed in September 2007. The Blackswift HTV-3X did not receive needed

funding and was canceled in October 2008.[3]

Current research under FALCON program is centered on X-41 Common Aero Vehicle (CAV), a common aerial platform for hypersonic ICBMs and cruise missiles, as well as civilian RLVs and ELVs. The prototype Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2) first flew on 22 April 2010; the second test flew 11 August 2011. Both flights ended prematurely.

Design and development

Past projects

The aim was always to be able to deploy a craft from the continental

United States, which could reach anywhere on the planet within one to

two hours. The X-20 Dyna-Soar

in 1957 was the first publicly acknowledged program—although this would

have been launched vertically on a rocket and then glided back to Earth, as the Space Shuttle does, rather than taking off from a runway. Originally, the Shuttle was envisaged as a part-USAF operation, and separate military launch facilities were built at Vandenberg AFB at great cost, though never used. After the open DynaSoar USAF program from 1957–1963, spaceplanes went black. In the mid-1960s, the CIA began work on a high-Mach spyplane called Project Isinglass. This developed into Rheinberry, a design for a Mach-17 air-launched reconnaissance aircraft, which was later canceled.[4]

According to Henry F. Cooper, who was the Director of the Strategic Defense Initiative

("Star Wars") under President Reagan, spaceplane projects consumed

$4 billion of funding in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s (excluding the Space

Shuttle). This does not include the 1950 and 1960s budgets for the

Dynasoar, ISINGLASS, Rheinberry, and any 21st-century spaceplane project

which might emerge under Falcon. He told the United States Congress in 2001 that all the United States had in return for those billions of dollars was "one crashed vehicle, a hangar queen, some drop-test articles and static displays".[5] Falcon was allocated US$170 million for budget year 2008.[6]

HyperSoar

The HyperSoar was an American hypersonic aircraft project developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

(LLNL). It was to be capable of flying at around Mach 12 (9,200 mph,

14,700 km/h), allowing it to transit between any two points on the globe

in under two hours. The HyperSoar is predicted to be a passenger plane

capable of skipping outside the atmosphere

to prevent it from burning up in the atmosphere. A trip from Chicago to

Tokyo (10,123 kilometers) would take 18 skips, or 72 minutes. It was

planned to use hydrocarbon-based engines outside the atmosphere and

experimental jet engine technology with testing to begin by 2010. Later,

the Hypersoar concept was acquired from LLNL by DARPA,[7] and in 2002 it was combined with the USAF X-41 Common Aero Vehicle to form the Falcon program.[8]

FALCON

The overall FALCON (Force Application and Launch from CONtinental United States) program announced in 2003 had two major components: a small launch vehicle for carrying payloads to orbit or launching the hypersonic weapons platform payload, and the hypersonic vehicle itself.[2]

Small Launch Vehicle

The DARPA FALCON solicitation in 2003 asked for bidders to do

development work on proposed vehicles in a first phase of work, then one

or more vendors would be selected to build and fly an actual launch

vehicle. Companies which won first phase development contracts of

$350,000 to $540,000 in November 2003 included:[9]

Hypersonic Weapon System

The first phase of the hypersonic weapon system development was won

by three bidders in 2003, each receiving a $1.2 to $1.5 million contract

for hypersonic vehicle development:[9]

- Andrews Space Inc., Seattle, Wash.

- Lockheed Martin Corp., Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Co., Palmdale, Calif.

- Northrop Grumman Corp., Air Combat Systems, El Segundo, Calif.

Lockheed Martin received the only Phase 2 HWS contract in 2004, to

develop technologies further and reduce technology risk on the program.[9]

Follow-on hypersonic program

Illustration of HTV-2 from DARPA

Following the Phase 2 contract, DARPA and the US Air Force continued to develop the hypersonic vehicle platform.

The program was to follow a set of flight tests with a series of hypersonic technology vehicles.[10]

The FALCON project includes:

The Hypersonic Cruise Vehicle (HCV) would be able to fly 9,000

nautical miles (17,000 km) in 2 hours with a payload of 12,000 lb

(5,500 kg).[15] It would fly at a high altitude and achieve speeds of up to Mach 20.[16]

Blackswift

The Blackswift was a proposed aircraft capable of hypersonic flight designed by the Lockheed Martin Skunk Works, Boeing, and ATK.[17]

The USAF states that the "Blackswift flight demonstration vehicle will be powered by a combination turbine engine and ramjet,

an all-in-one power plant. The turbine engine accelerates the vehicle

to around Mach 3 before the ramjet takes over and boosts the vehicle up

to Mach 6."[18]

Dr. Stephen Walker, the Deputy Director of DARPA's Tactical Technology

Office, will be coordinating the project. He told the USAF website,

I will also be communicating to Lockheed Martin and Pratt &

Whitney on how important it is that we get the technical plan in

place ... I'm trying to build the bridge at the beginning of the

program—to get the communication path flowing.

The Falcon program has announced the hypersonic horizontal take-off

Blackswift/HTV-3X. It is also launching the HTV-2 off the top of a

rocket booster.[19]

Falcon seems to be converging from two directions, on the ultimate goal

of producing a hypersonic aircraft which can take off and land from a

runway in the USA, and be anywhere in the world in an hour or two.

Falcon is methodically proceeding toward a Hypersonic Cruise Vehicle.

Dr. Walker stated,

We need to fly some hypersonic vehicles—first the expendables, then

the reusables—in order to prove to decision makers that this isn't just a

dream… We won't overcome the skepticism until we see some hypersonic

vehicles flying.

The HTV-3X activates its turbojets in transonic flight…

|

|

…then ignites its scramjets for the hypersonic phase |

|

Simulation of the Falcon HTV-3X [20] |

|

In October 2008 it was announced that HTV-3X or Blackswift did not

receive needed funding in the fiscal year 2009 defense budget and had

been canceled. The Hypersonic Cruise Vehicle program will continue with

reduced funding.[3][21]

Flight testing

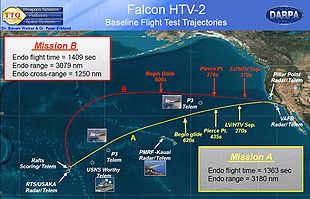

Flight Test trajectories for HTV 2a and 2b

DARPA had two HTV-2s built for two flight tests in 2010 and 2011. The Minotaur IV light rocket is the booster for the HTV-2 with Vandenberg Air Force Base

serving as the launch site. DARPA planned the flights to demonstrate

thermal protection systems and aerodynamic control features.[3][12] Test flights were supported by NASA, the Space and Missile Systems Center, Lockheed Martin, Sandia National Laboratories and the Air Force Research Laboratory's (AFRL) Air Vehicles and Space Vehicles Directorates.

The first HTV-2 flight was launched on 22 April 2010.[12] The HTV-2 glider was to fly 4,800 miles (7,700 km) across the Pacific to Kwajalein at Mach 20.[19]

The launch was successful, but the first mission was not completed as

planned. Reports stated that contact had been lost with the vehicle nine

minutes into the mission.[22][23]

In mid-November, DARPA revealed that the test flight had ended when the

computer autopilot had "commanded flight termination". According to a

DARPA spokesman, "When the onboard system detects [undesirable or unsafe

flight] behavior, it forces itself into a controlled roll and pitchover

to descend directly into the ocean." Reviews found that the craft had

begun to roll violently.[24]

A second flight was launched on 11 August 2011. The unmanned Falcon

HTV-2 successfully separated from the booster and entered the mission's

glide phase, but again lost contact with control about nine minutes into

its planned 30-minute Mach 20[citation needed]

glide flight. Initial reports indicated it purposely impacted the

Pacific Ocean along its planned flight path as a safety precaution.[25][26][27] Some analysts thought that the second failure would result in an overhaul of the Falcon program.[28]

Refocus

In July 2013, DARPA decided it would not conduct a third flight test

of the HTV-2 because enough data had been collected from the first two

flights, and another test was not thought to provide any more usable

data for the cost. The tests provided data on flight aerodynamics and

high-temperature effects on the aeroshell. Work on the HTV-2 would

continue to summer 2014 to provide more study on hypersonic flight. The

HTV-2 was the last active part of the Falcon program. DARPA has now

changed its focus for the program from global/strategic strike to

high-speed tactical deployment to penetrate air defenses and hit targets

quickly from a safe distance.[29]

See also

References

US looks for answers after hypersonic plane fails

FALCON

Force Application and Launch from CONUS Broad Agency Announcement (BAA)

PHASE I Proposer Information Pamphlet (PIP) for BAA Solicitation 03-35. DARPA, 2003.

"Falcon Technology Demonstration Program HTV-3X Blackswift Test Bed". DARPA, October 2008.

Isinglass. astronautix.com

Cooper Testimony. tgv-rockets.com

Space Weapons Spending in the FY 2008 Defense Budget. cdi.org

https://newsline.llnl.gov/employee/articles/2001/10-05-12-hypersoar.html

http://www.designation-systems.net/dusrm/app4/x-41.html.

USAF DARPA FALCON Program. Air-attack.com. Retrieved: 2012-02-05.

"Falcon Technology Demonstration Program: Fact Sheet"[dead link]. DARPA, January 2006.

"US hypersonic aircraft projects face change as Congress urges joint technology office". Flight International, 30 May 2006.

"First Minotaur IV Lite launches from Vandenberg" Archived April 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.. U.S. Air Force, 22 April 2010.

"US hypersonic glider flunks first test flight". AFP news agency, 27 March 2010.

Graham Warwick (24 April 2010). "DARPA's HTV-2 Didn't Phone Home". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

"Propulsion, Materials Test Successes Put Positive Spin on Falcon Prospects". Aviation Week, 22 July 2007.

Falcon HTV-2 Archived September 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.. DARPA

Warwick, Graham (24 July 2008). "Boeing Joins Lockheed Martin On Blackswift". Aviation Week, 24 July 2008. Retrieved: 28 March 2010.

Lorenz III, Philip (17 May 2007). "DARPA official: AEDC 'critical' to hypersonics advancement". Arnold Air Force Base. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

Little, Geoffrey. "Mach 20 or Bust, Weapons research may yet produce a true spaceplane". Air & Space Magazine, 1 September 2007.

DARPA promotional video of HTV-3X

Trimble, Stephen. "DARPA cancels Blackswift hypersonic test bed". Flight Global, 13 October 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

Clark, Stephen. "New Minotaur rocket launches on suborbital flight". spaceflightnow.com, 23 April 2010.

Waterman, Shaun. "Plane's flameout may end space weapon plan". Washington Times, 22 July 2010.

Waterman, Shaun (25 November 2010). "Pentagon to test 2nd near-space strike craft". The Washington Times. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

Rosenberg, Zach. "DARPA loses contact with HTV-2". Flight International, 11 August 2011.

"DARPA HYPERSONIC VEHICLE ADVANCES TECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE". DARPA, 11 August 2011.

Norris, Guy. "Review Board Sets Up to Probe HTV-2 Loss". Aviation Week, 12 August 2011.

[1]. BBC NEWS, 11 August 2011.

External links

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hypersonic Technology Vehicle HTV-2 reentry (artist's impression)

Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2) is a crewless,[1] experimental rocket glider developed as part of the DARPA Falcon Project capable of flying at 13,000 mph (21,000 km/h).[2] It is a test bed for technologies to provide the United States with the capability to reach any target in the world within one hour using an unmanned hypersonic bomber aircraft.[3]

Development

The Falcon HTV-1 program, which preceded the Falcon HTV-2 program,

was conducted in April, 2010. The mission ended within nine minutes from

launch.[3] Both these missions are funded by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to help develop hypersonic technologies and to demonstrate its effectiveness.[4] Under the original plan, HTV-1 was to feature a hypersonic lift-to-drag ratio (L/D) of 2.5, increasing to 3.5-4 for the HTV-2 and 4-5 for the HTV-3. The actual ratio of HTV-2 was estimated to be 2.6.[5]

HTV-2 was to lead to the development of an HTV-3X vehicle, known as Blackswift,

which would have formed the basis for deployment around 2025 of a

reusable Hypersonic Cruise Vehicle, an unmanned aircraft capable of

taking off from a conventional runway with a 5,400 kg (12,000 lb)

payload to strike targets 16,650 km away in under 2h. The HCV would have

required an L/D of 6-7 at M10 and 130,000 ft (40,000m).[6]

Design

DARPA's Falcon Hypersonic Technology Vehicle-2

Development of protection structures that are tough and light-weight,

development of an aerodynamic shape that has a high lift to drag ratio,

development of automatic navigation control systems etc. were some of

the initial technical challenges that had been overcome in the final

design.[4]

The various departments involved in designing the vehicle included

aerothermodynamics, materials science, hypersonic navigation, guidance

and control systems, endo- and exo-atmospheric flight dynamics,

telemetry and range safety analysis. The craft could cover 17,000

kilometres, the distance between London and Sydney, in 49 minutes.[3]

Flight testing

Launch of HTV-2a on a Minotaur IV Lite rocket

Falcon HTV-2 baseline flight test trajectories

The HTV-2's first flight was launched on 22 April 2010.[7] The HTV-2 glider was to fly 4,800 miles (7,700 km) across the Pacific to Kwajalein at Mach 20.[8] The HTV-2 was boosted by a Minotaur IV Lite rocket launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base,

California. The flight plan called for the craft to separate from the

launch vehicle, level out and glide above the Pacific at Mach 20.[1][3] Contact was lost with the vehicle nine minutes into the 30-minute mission.[3][9][10]

In mid-November, DARPA stated that the first test flight ended when the

computer autopilot "commanded flight termination" after the vehicle

began to roll violently.[11]

A second flight was initially scheduled to be launched on August 10, 2011, but bad weather forced a delay.[12]

The flight was launched the following day, on 11 August 2011. The

unmanned Falcon HTV-2 successfully separated from the booster and

entered the mission's glide phase, but again lost contact with control

about nine minutes into its planned 30-minute Mach 20 glide flight.

Initial reports indicated it purposely impacted the Pacific Ocean along

its planned flight path as a safety precaution.[13][14][15]

Future development

DARPA does not plan to conduct a third flight test of the HTV-2. The

decision was made because substantial data was collected from the first

two flights, and a third was not thought likely to provide any

additional valuable data for the cost. The first flight provided data in

aerodynamics and flight performance, while the second provided

information about structures and high temperatures. Experience gained

from the HTV-2 will be used to improve hypersonic flight.

Work on the HTV-2 will continue to Summer 2014 to capture technology

lessons and improve design tools and methods for high-temperature

composite aeroshells.[16][needs update]

See also

References

"Experimental aircraft to launch Wednesday from Vandenberg". sanluisobispo.com. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

"A Rocket-Airplane Will Fly Mach 20 Today, But Won't Be Taking Passengers". Jaunted. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

"Hypersonic plane could fly Sydney to London in 49 minutes". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 August 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

"Falcon Hypersonic Technology Vehicle HTV-2". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

http://scienceandglobalsecurity.org/archive/2015/09/hypersonic_boost-glide_weapons.html

http://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/does-us-need-1bn-hypersonic-test-area-after-htv-2-failure-341672/

"First Minotaur IV Lite launches from Vandenberg" Archived April 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.. U.S. Air Force, 22 April 2010.

Little, Geoffrey. "Mach 20 or Bust, Weapons research may yet produce a true spaceplane". Air & Space Magazine, 1 September 2007.

Clark, Stephen. "New Minotaur rocket launches on suborbital flight". spaceflightnow.com, 23 April 2010.

Waterman, Shaun. "Plane's flameout may end space weapon plan". Washington Times, 22 July 2010.

Waterman, Shaun (25 November 2010). "Pentagon to test 2nd near-space strike craft". The Washington Times. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

"Pentagon's Hypersonic Aircraft Test Flight Delayed Due to Bad Weather". International Business Times. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

Rosenberg, Zach. "DARPA loses contact with HTV-2". Flight International, 11 August 2011.

"DARPA HYPERSONIC VEHICLE ADVANCES TECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE". DARPA, 11 August 2011.

Norris, Guy. "Review Board Sets Up to Probe HTV-2 Loss". Aviation Week, 12 August 2011.

External links